Invisible Player – The History of Rosemary Sanders

The Invisible Player Trailer

Donations to the “Invisible Player Fund” and do not go towards the South Bend Symphony Annual Fund.

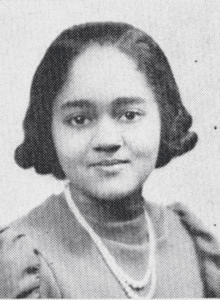

Rosemary Sanders was born in 1921 in Chicago and at age five moved with her parents to South Bend, Indiana. Her mother, Helen, worked for Gertrude Oliver Cunningham who recognized Rosemary’s talent and bought her a Stradivarius in the 1930s. With no African American string teachers in South Bend at the time, Rosemary studied privately in Chicago at the Sherwood Music School. She was a member of the Riley High School Orchestra, serving as secretary. She auditioned and was accepted into the South Bend Symphony in 1940, where she played for 15 years, sitting in the last row of the second violin section. She performed during a time when segregation was prevalent in South Bend; the city’s cultural and social institutions, hotels, and restaurants did not admit African Americans. Rosemary’s name was never listed in any Symphony programs, and in formal photographs she was seated behind the orchestra, with only her head visible. In addition to her Symphony membership, she taught private students from Notre Dame and performed at her home church, Greater St. John’s Baptist Church. She was a composer, teacher, and lover of music. She passed in 2017 at the age of 95. We honor her contributions to the South Bend Symphony Orchestra.

Invisible Player By Dr. Marvin V. Curtis

In 1940, 19-year-old Rosemary Sanders became the first African American musician in the South Bend Symphony Orchestra and probably in America. This project, Invisible Player, is designed to present the historical narrative of Rosemary Sanders and highlight the racial barriers African Americans face in American orchestras. The film uses Rosemary’s story as a jumping off point to explore where the American orchestral industry is today, how we got here, and possible paths forward.

Sanders prepared for her audition with years of private study with South Bend’s concertmaster, the lead violinist of the Symphony. During high school, she traveled from South Bend, Indiana, to Chicago with her mother on the segregated South Shore train line to study as the only African American student at the Sherwood School of Music at Columbia College. Through the generosity of her family’s employer, Gertrude Oliver Cunningham, she was given a Stradivarius violin, one of the most prized string instruments in the world. Despite her obvious talent as a violinist, when she joined the South Bend Symphony, she was assigned to the last seat in the second violin section. The audience could not even see her. For the fifteen years she performed with the orchestra, her name was never listed in the program. She was never included in formal pictures of the orchestra. Her musical background and first-class instrument notwithstanding, she was never allowed to advance from the last seat, where she was invisible to the audience. Upon her leaving the orchestra, the next African American member of the South Bend Symphony would not join until 1995, 32 years later.

With Rosemary excluded from orchestral history, records list Denver Symphony bassist Charles Burrell as the first African American player in an American orchestra in 1949. The deliberate exclusion of Rosemary Sanders from the history of the South Bend Symphony is emblematic of racist policies of the Jim Crow era. Yet many these policies have persisted long past the formal end of Jim Crow, and have resulted in the continued racial disparity between African American players and white players. Even when included as members of American orchestras, many players find themselves to be “invisible” among their fellow musicians.

In 2014, there were 1,224 orchestras in the US, and African Americans comprised just 1.8% of the players, based on data provided by the League of American Orchestras. In 2024, there were roughly 2,000 orchestras in America, and the number of African American players had grown to 2.4%, while other racial groups, such as Latino/Hispanic players, expanded from 2.5% to 4.8%, and Asian players grew from 9.2% to 11%.

The history of Rosemary Sanders and South Bend in Invisible Player will show why American orchestras have remained so out-of-step with the demographics of their communities. The film explores Sanders’ background and life in South Bend, her relationship with her benefactor, Gertrude Oliver Cunningham, her symphony experience, and how she dealt with the racial climate in the city after leaving the symphony. Her life story exemplifies the continuing lack of diversity in American orchestras. Our project covers topics such as the past and present racial challenges that African Americans face and have faced, including the lack of arts education in communities of color and its effects on the pipeline of potential players. I survey solutions that are being developed to address the problem. Orchestras still look much as they did when Rosemary Sanders was playing. Will things ever change?

I am traveling the country looking for answers. I began working locally in the archives with the South Bend History Museum and the St. Joseph County Library. Working with the film team of videographer Ryan Blaske and director Chuck Fry and my co-producer Justus Zimmerman, we have recorded extensive interviews with Sanders’ daughter, Helen Binion-Ursey. We visited the Detroit Conference of the Sphinx Organization, whose mission is to address the systemic lack of access in classical music by Black and Latino communities, and interviewed many participants, including Aaron Dworkin, its founder. Simon Woods, president and CEO of the League of American Orchestras, the 700-member service organization, sat for an interview at their Houston conference. Former Executive Director Lee Koonce and new Executive Director Alexander Laing of the African American Gateways Music Festival Orchestra gave their insight. Lee Pringle, the founder of The Colour of Music Festival of Charleston, South Carolina, outlined his distinctive views. Interviews are being scheduled and conducted with many African American players and managers who are navigating the current landscape and dealing with current challenges. All share their hopes and fears about the future. They are charting a course whereby American orchestras can reach their full, diverse potential.

The story of Invisible Player will be told in a 90-minute film, with me serving as guide, narrator, and executive producer. Since Sander’s history was not readily available, I researched her South Bend story using primary source materials provided by her daughter and Sander’s writings. Additional research has been conducted into the racial climate that led to the inclusion of African Americans in the five largest American orchestras. This complicated history focuses on the orchestral and musician union climate that left many of these players feeling invisible. I’ve had discussions with arts leaders concerning the role of arts education, access, and different schools of thought for diversifying the orchestral landscape. These discussions have yielded contentious viewpoints revolving around the fundamental conflict: should African American ensembles be self-sustaining, or should players pursue immersion into the orchestral landscape, or is there a compromise? The South Bend Symphony will provide a musical soundtrack utilizing music Sanders would have performed, as well as works of African American composers. We have commissioned a new work by African American violinist and composer Jessica Carter of South Bend.

Invisible Player seeks to expose an injustice, examine the rationale for that injustice, and offer solutions to create a more equitable and inclusive art form. This film tackles a subject with broad implications for the future. I anticipate very extensive dissemination of the film, beginning with its submission to film festivals. From there, it is designed for viewing everywhere high-quality documentaries are available. The film is designed to be a tool for American orchestras to acknowledge the past and make changes for a positive future.

Viewpoint: Classically trained Rosemary Sanders of South Bend was the Invisible Player

Marvin Curtis

Published to the South Bend Tribune

The number of African Americans in American Symphony Orchestras continues to be dismal. Blame must be placed on the discriminatory practices of musician unions and concert halls that practiced segregation. Those African American composers who wrote in the classical style were overlooked and their music was not valued by white music critics and historians.

Most classically trained African American musicians were discouraged from pursuing a career with our American symphonies; however, a select few were able to break the color barrier, only to be subjected to segregation on concert tours, particularly in the South. History records the first African American to join an American orchestra was violinist Jack Bradley as a member of The Denver Symphony in 1946.

The South Bend Symphony Orchestra’s first African American member was Rosemary Sanders, who auditioned and was admitted in 1940. Born in Chicago in 1921, Sanders moved with her parents to South Bend at age 5. Her mother, Helen, worked as head of the household staff for Gertrude Oliver Cunningham (daughter of J.D. Oliver), who recognized Rosemary’s talent and bought her a Stradivarius violin. With no African American string teachers in South Bend at the time, Sanders studied privately with George Zigmont Gaskas, concertmaster of the South Bend Symphony and later founder and conductor of the Elkhart Symphony. She was also a student at the Sherwood Music School in Chicago, in high school and after graduation.

Sanders grew up on the southeast side of South Bend and attended Riley High School from 1935-1939. She was the only African American student at the school, and served as secretary/treasurer as a member of the school orchestra.

She played in the Symphony Orchestra for 20 years, sitting in the last row of the second violin section. But her name was never listed in any programs. She appears in the 1943-1944 formal photograph of the Symphony, not sitting with the orchestra members, but seated behind the orchestra with only her head showing. She performed during a time when segregation was prevalent in South Bend and the city’s cultural and social institutions, hotels and restaurants did not admit African Americans.

Sanders taught private students from Notre Dame and performed at her home church, Greater St. John Missionary Baptist Church. She was a composer, teacher and lover of music. She passed in 2017 at age 95. She married Graham Henry Sr. of Old Harbor Bay, Jamaica, West Indies. From this marriage two children survive, Graham M. Henry and Helen Ursery-Binion.

The lack of African American musicians in American orchestras is well-documented. Of those considered the “Big Five” — because of their history and scope — the admittance of African American players is depressing. The Cleveland Orchestra, organized in 1918, hired cellist Donald White in 1957; The New York Philharmonic, organized in 1842, hired violinist Sanford Allen in 1962; The Philadelphia Orchestra, organized in 1900, hired violinist Booker Rowe in 1968; The Boston Symphony, organized in 1881, hired harpist Ann Hobson in 1969; and The Chicago Symphony, organized in 1891, hired their first African American player in trumpeter Tage Larsen in 2002.

According to the American Symphony Orchestra League, African Americans account for only 1.8 percent of the nation’s orchestra players in 2014, and that figure had not grown since. In 1995, The South Bend Symphony Orchestra hired its second African American player. She is bassist Diana Ford, who still performs today. The South Bend Symphony has had four African American players since then.

Our American cultural institutions have perpetuated racist injustices in the past, but the tide is turning. Equity, diversity and inclusion are being seen not as a threat to the status quo, but as a way to heal and educate our society and celebrate the wealth of talent in our country.

The South Bend Symphony Orchestra is celebrating Rosemary Sanders this year in their 90th anniversary program book. To continue the recognition, the History Museum will be unveiling a display about Sanders on June 13 as part of the African American Legacy Award Luncheon.

How nice it would have been if Sanders had been acknowledged during her lifetime with just her name in the program. The South Bend Symphony Orchestra is making sure that Rosemary Sanders will no longer be invisible, but celebrated for her talent and perseverance.

Sphinx Conference Panel

Discussion Panel at the South Bend History Museum

Experience Michiana Interview

About Marvin V. Curtis

Marvin V. Curtis is the Coordinator of Arts Equity and Public Art for the City of South Bend, Indiana. He is Dean Emeritus and Professor Emeritus in Music of the Ernestine M. Raclin School of the Arts at Indiana University South Bend. He was the first African American composer to receive a commission to write a choral composition for a Presidential Inauguration. In 1993, before the administration of the oath of office to Vice President Albert Gore, Jr., his choral work, City on the Hill premiered with The Philander Smith Collegiate Choir of Little Rock, Arkansas, and The United States Marine Band at the Inaugural Ceremonies for President William Jefferson Clinton. The choral work is held in the Clinton Library and various archives nationwide. It is part of the Smithsonian Institute’s National African American Project Archives.

A native of Chicago, Illinois, he holds degrees from North Park University (BM), The Presbyterian School of Christian Education (MA), and The University of the Pacific (EdD) with a focus in Music Education. He undertook additional studies at Westminster Choir College and The Juilliard School of Music, and he was a Ford Foundation Fellow studying in West Africa at the University of Ghana at Legon.

As a composer and conductor, he has received numerous commissions from colleges and churches, including the 100th anniversary anthem for Morris Brown College in Atlanta, the Inauguration Anthem for the creation of Clark Atlanta University, and the 125th anniversary of North Park University in Chicago. He composed music for the documentary A Road to Hope, which earned him the Bronze Award for Best Original Song by the Prestige Film Festival. In 2021, he served as lead composer on the documentary Then, Now, and Always…The St. Joseph River Story produced by WNIT Public Television. He co-wrote music for the theatrical production A Place to be Somebody: The Story of Charles Gordone with Delshawn Taylor as part of the Bicentennial Celebration of Indiana.

He serves as conductor of The South Bend Symphonic Choir, a community choir that performed a 90-minute concert at The White House on December 21, 2009. He has served for over 60 years as a church musician and is currently the Director of Music at St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church in South Bend. He has led community choirs, facilitated workshops on choral music and African American music/education, published in scholarly journals, and served as guest conductor for choral festivals nationwide.

Dr. Curtis is a member of the Board of Trustees of North Park University, his Alma Mater. He currently holds the position of President of The South Bend Symphony Orchestra Board of Directors, The 100 Black Men of Greater South Bend, and Uzima Drum and Dance Company. He serves on the boards of The St Joseph County Library, The Fischoff National Chamber Music Association, The South Bend History Museum, and The South Bend Museum of Art. He served for 12 years as the National Scholarship Chair for the National Association of Negro Musicians.

His honors include The South Bend Hall of Fame, The Drum Major Award from the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Foundation, The University of North Carolina’s Board of Governors Award for Excellence in Teaching, The Roland Carter Living Legends Award from the Hampton Minister’s Conference for his music, and The African American Award from the History Museum of South Bend.

About Justus Zimmerman

Justus Zimmerman is the CEO and Executive Director of the Austin Symphony Orchestra. Prior to 2025, he served as the Executive Director of the South Bend Symphony Orchestra, where his collaborative approach set the stage for unprecedented growth.

By building a dynamic Marketing Department from the ground up, South Bend achieved record-breaking subscription and single-ticket sales and received accolades for award-winning customer service, leading to overall ticket sales growth surging more than 70% from pre-pandemic levels. Similarly, a refocusing of the Development Department to prioritize donor relationships above transactions increased contributed income nearly 90%.

Justus strategically reinvested in community collaborations in South Bend, like bringing live music back to The Nutcracker for the first time in 20 years, helping solidify the symphony’s reputation as the leading arts institution in the area and broadening the coalition of supporters. Collaborations and cultural exchanges have touched scores of organizations, including the Civic Theatre, the local Lyric Opera, the LINKS, 100 Black Men, the Jewish Federation, the Boys and Girls Club, Uzima! African Drum & Dance, and many more.

Believing deeply in the power of an orchestra’s people, Justus has worked tirelessly to build relationships with the musician core. This inclusive approach led to long-tenured musicians expressing greater fulfillment and enjoyment, with one noting, “I haven’t felt this way about symphonic music since I was a teen”; the swift negotiation of a 4-year collective bargaining agreement, now held up as a model by musicians in other midwest regional orchestras; and extraordinary artistic opportunities, from performing with Yo-Yo Ma to commissioning and premiering new works by acclaimed composers like Anna Clyne.

Prior to his tenure in South Bend, Justus served as the Marketing Director for the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. There, he implemented innovative, digital-first marketing strategies that increased revenue by 35% despite significant budget cuts. He co-founded Chamber Music LA to advocate for the art form and collaborated with the Inner City Youth Orchestra of Los Angeles to support young Black and Latino musicians.

Outside of his professional life, Justus is an avid climber and outdoor enthusiast, known for “packing out more trash than he brings in.” As much as he loves time alone in the mountains, he cherishes time with his wife, Liz, and their two young daughters.

About Ryan Blaske

Ryan Blaske is the founder of Blaske Studio, where he leads documentary and commercial film projects that balance emotional depth with strong visual design. Based in South Bend, Indiana, Ryan draws inspiration from the Midwest and the stories that shape its people and places. His acclaimed film Big Enough, Small Enough: South Bend in Transition captures a city at a crossroads, reflecting on race, redevelopment, and identity in a rapidly changing landscape. He has collaborated with The Washington Post, the University of Notre Dame, A&E, Whirlpool, and Adobe, working across formats to create everything from short-form branded content to long-form narrative pieces. Ryan’s work has been recognized with multiple ADDY Awards and is marked by a commitment to authenticity, craft, and impact. Through Blaske Studio, he continues to seek out stories that matter—stories that reflect who we are and where we’re headed.